One year later: Hereâs how a committed community stepped up to save our nationâs oldest free Black settlement

STATEN ISLAND, N.Y. — This time last year, Julie Moody Lewis stood outside the weathered, century-old white ranch home that once housed the Sandy Ground Historical Society Museum, seeking help from anyone in the community who would listen. Inundated with floodwaters, riddled with mold and a crumbling roof, the structure’s future was uncertain.

But there was more than just the museum’s structural challenges that had befallen Sandy Ground, which is the oldest free Black settlement in the nation still inhabited by decedents of its pioneers. In fact, this community — founded by Moses K. and Silas K. Harris in 1828 — was no stranger to hardship.

The first sign the historic site was in great need of help was when Sandy Ground showed up on a national cultural landscape report deemed “threatened and at-risk” in December 2021.

Interim executive director of the Sandy Ground Historical Society David McGoy poses with Julie Moody Lewis, president of the historical society, in front of the museum on Monday, Dec. 4, 2023. (Staten Island Advance/Jason Paderon) Jason Paderon

The Sandy Ground Historical Society had lost its not-for-profit status, inhibiting the organization from receiving any funding, which was greatly needed to pay a stack of overdue bills and make repairs to the museum, located at 1538 Woodrow Rd. In addition, the historic community was in need of new leadership, and its historians were seeking to pass the torch of preservation to a new generation.

Moody Lewis, the historical society’s president, knew she needed help, and she wasn’t afraid to ask. She knew Sandy Ground was a significant part of not only Staten Island’s history, but New York’s and the United States’ histories as well. That’s when she turned to the Advance/SILive.com, which launched a journalistic initiative on Feb. 9, 2023, to bring awareness to the importance of preserving Sandy Ground.

“In the beginning, it was like, ‘How are we going to do this?’ How is this going to happen?’ Once they [the Advance/SILive.com and community groups] stepped in, it became a work in progress. All the right people were right there in place,” she said.

Interim executive director of the Sandy Ground Historical Society, David McGoy poses, with the historical society’s president, Julie Moody Lewis, in front of the museum on Monday, Dec. 4, 2023. (Staten Island Advance/Jason Paderon) Jason PaderonJason Paderon

“I’m a believer in God. And I know he had his hand in it because it looked abysmal at one point. We got the backing of a lot of people, many of whom didn’t even know about us, and they wanted to help. At that point, I told my board, ‘We’re not going to fall. Staten Island is not going to let us fall.’ We are part of the borough. We’re part of the fabric of the borough. Sandy Ground has always been resilient, and the Historical Society is resilient too,” she said.

Scaran heating and plumbing came to the rescue to turn off the water at the Sandy Ground Museum on Feb.14, 2023. (Staten Island Advance/Jan Somma-Hammel)

A LOT HAS CHANGED IN ONE YEAR

Immediately after the first story published, Scaran Heating & Air Conditioning shut down the water main to resolve the flooding conditions in the museum.

Soon after, the South Shore Rotary Club pledged its support. Lynne Persing, chief operating officer of the South Shore Rotary Club, put Moody Lewis in touch with Mona Ghanem, vice president and branch manager of Northfield Savings Bank in Great Kills, who helped the group obtain information needed to reestablish the Historical Society’s 501(c)(3) not-for-profit status. Next, Rep. Nicole Malliotakis (R-Staten Island/Brooklyn) contacted the IRS on the Historical Society’s behalf to have the application expedited.

Sylvia Moody D’Alessandro, former executive director of the Sandy Ground Historical Society, listens in at the South Shore Rotary Club’s weekly meeting at the Old Bermuda Inn in Huguenot on Thursday, March 23, 2023. (Staten Island Advance/Jason Paderon) Jason PaderonJason Paderon

In October 2023, the New York Landmarks Conservancy — a decades-old organization that provides financial and technical assistance to owners of historic properties — issued a grant to the Sandy Ground Historical Society to help restore the museum. The first step consisted of a mold investigation.

Behind the scenes, two of Staten Island’s largest not-for-profits worked to save Sandy Ground in many different ways, including helping identify a candidate for interim executive director, which was greatly needed as Sylvia Moody D’Alessandro — Moody Lewis’ mother who has been at the helm of the organization for many years — retired.

The community came together to help rebuild Sandy Ground.(Steve White for the Staten Island Advance)

Soon after, the Historical Society Board voted in David McGoy, who grew up in the West Brighton Houses, and whose aunt was a longtime friend of Moody D’Alessandro.

“We really have to focus on assessing the situation, and really be able to understand the way forward. I think we know what the challenges are, and I think we need to quantify the challenges, and name them in specific ways that have action steps connected to them,” said McGoy, now a resident of Livingston and director of strategic growth for Cause Effective, which helps revitalize not-for-profits.

One initial step is the mold remediation of the museum. “We need to know what it’s going to take to get the mold out of there, and what else is it going to take besides money for this to be inhabitable and useful?” said McGoy, noting the mold study is ongoing.

The Sandy Ground Historical Society Museum’s roof is in great need of repair. (Staten Island Advance/Jason Paderon)Jason Paderon

McGoy said his first order of business is to take the many artifacts — which includes everything from blacksmith tool’s from Joseph Bishop’s longtime Sandy Ground blacksmith shop, to tintype photos of early settlers of the community — to be displayed in temporary exhibits that will be set up across Staten Island and beyond.

“I want to get back to the mission. We get inquiries all the time about people who want speakers and they have research requests about Sandy Ground, and we want to get the story out there,” said McGoy. “I think the idea of setting up temporary exhibits with some partners is something I’d like to move on sooner rather than later, as well as setting up some online programming where we can do lectures, and really share the history with people who are interested in it.”

Inside the Sandy Ground Historical Society Museum, which is uninhabitable. (Staten Island Advance/Jan Somma-Hammel)

To kick off fundraising efforts, Northfield Bank Foundation gave $25,000, and the Staten Island Foundation gave $50,000.

But that’s just the start.

McGoy said he will be launching a “large-scale” fundraising campaign later this year to raise money needed to breathe new life into Sandy Ground.

Two baymen’s cottages on Bloomfield Road still stand on Staten Island. Here they are on Tuesday, Jan. 31, 2023. (Staten Island Advance/Jason Paderon) Jason Paderon

THE PLAN

Last week, McGoy introduced a four-part, long-term plan that will unfold over the next year:

- Governance: This includes confirming the not-for-profit’s legal status, reviewing and updating the Sandy Ground Historical Society’s bylaws; creating and implementing a board development plan; convening an advisory committee; and launching a search for a permanent executive director.

- Finances: This will include conducting a financial assessment, creating an operating budget and financial plan, and establishing financial management and reporting systems.

The Rossville A.M.E. Zion Church, built on Bloomingdale Road in 1897. (Staten Island Advance/Jason Paderon)Jason Paderon

- Space: This will entail conducting an extensive mold study and remediation, assessing space needs (repair/renovation), and creating a capital plan and budget.

- Community engagement: McGoy said he plans to set up temporary exhibits across the borough and beyond made up of Sandy Ground artifacts, which are currently boxed in a storage facility. In addition, he plans to create online programming, plan public events, such as the traditional barbecues the community was known for, and recover missing artifacts.

Joseph W. Bishop’s blacksmith shop operated from a wooden barn in Sandy Ground for over 125 years. It eventually burned down following a suspicious fire. (Advance composite)

SANDY GROUND MEMBERS ARE GRATEFUL

The Sandy Ground Historical Society is grateful for everyone who has stepped up to join the revitalization effort.

“I want to thank everyone from the bottom of my heart and from our families, the families of Sandy Ground,” said Tom Wilson, a Sandy Ground Historical Society board member. “It’s been a journey…and with your help we are going to see bigger and brighter things.”

Julie Moody Lewis stands with William Henrique, an inspector with Windsor Environmental, who tested the air for mold inside the Sandy Ground Historical Museum at 1538 Woodrow Rd. on Monday, Oct. 16, 2023. (Staten Island Advance/Jan Somma-Hammel)

Said Julie Moody Lewis: “My mother [Sylvia D’Alessandro] and I are very grateful. … We understand how important the history is, and that it needs to be put in a sustainable form to move forward.”

The Temple family whose roots are in Sandy Ground reunited in 2022 to celebrate Richard Temple’s 80th birthday. (Courtesy of Charlotte Griggs)

SANDY GROUND HISTORY

Settled in the 1820s, Sandy Ground is the third recorded community in New York where African Americans owned land, according to city Landmarks Preservation Commission.

Sandy Ground Historical Society President Julie Moody Lewis makes a presentation at the South Shore Rotary Club’s weekly meeting at the Old Bermuda Inn in Huguenot on Thursday, March 23, 2023. (Staten Island Advance/Jason Paderon) Jason PaderonJason Paderon

The Harris brothers from New Jersey initially came to the area to work as gardeners in the 1820s. They also owned property in Manhattan, according to Moody Lewis. Early on, the community was most known for its fertile strawberry crops that would yield an abundance of the fruit.

Sylvia D’Alessandro giving coloring books out about Sandy Ground in this Advance photo from 1998.

In the 1850s African American oystermen from Maryland became attracted to the area because of the abundant oyster beds of the Raritan Bay. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the community became self-sufficient and thrived as it housed a range of professionals and tradesmen, from blacksmiths and store owners to teachers and midwives. Soon, Sandy Ground became a community where African Americans found prosperity and freedom from persecution.

Today, Sandy Ground is tucked away amid dense housing and paved roadways that serve as a main bus route for two public schools. But, if you look closely while driving along Woodrow or Bloomingdale roads, you can see the remaining homes and landmarked structures in Sandy Ground that still exist today.

In this undated photo are Dr. Evelyn Mangin’s grandmother Helena Hyde Bishop with her daughters at church: Alfredia Johnson, Helena Hyde Bishop, Helena Snyder, and Rosanna Wilson. (Courtesy of Dr. Evelyn Mangin)Courtesy of Dr. Evelyn Mangin

There are several properties in the community designated New York City landmarks: two tan clapboard Baymen’s cottages on Bloomingdale Road, which are 120-year-old-plus homes once owned by the prosperous oystermen who settled in the community in the 1850s; the A.M.E. Zion Church, built on Bloomingdale Road in 1897; the Rev. Isaac Coleman and Rebecca Gray Coleman home at 1482 Woodrow Rd.; and the Rossville A.M.E. Zion Church Cemetery on Crab Tree Avenue — a peaceful respite where both weathered and newer headstones tell the story of the community’s pioneers who once lived, worked and thrived there.

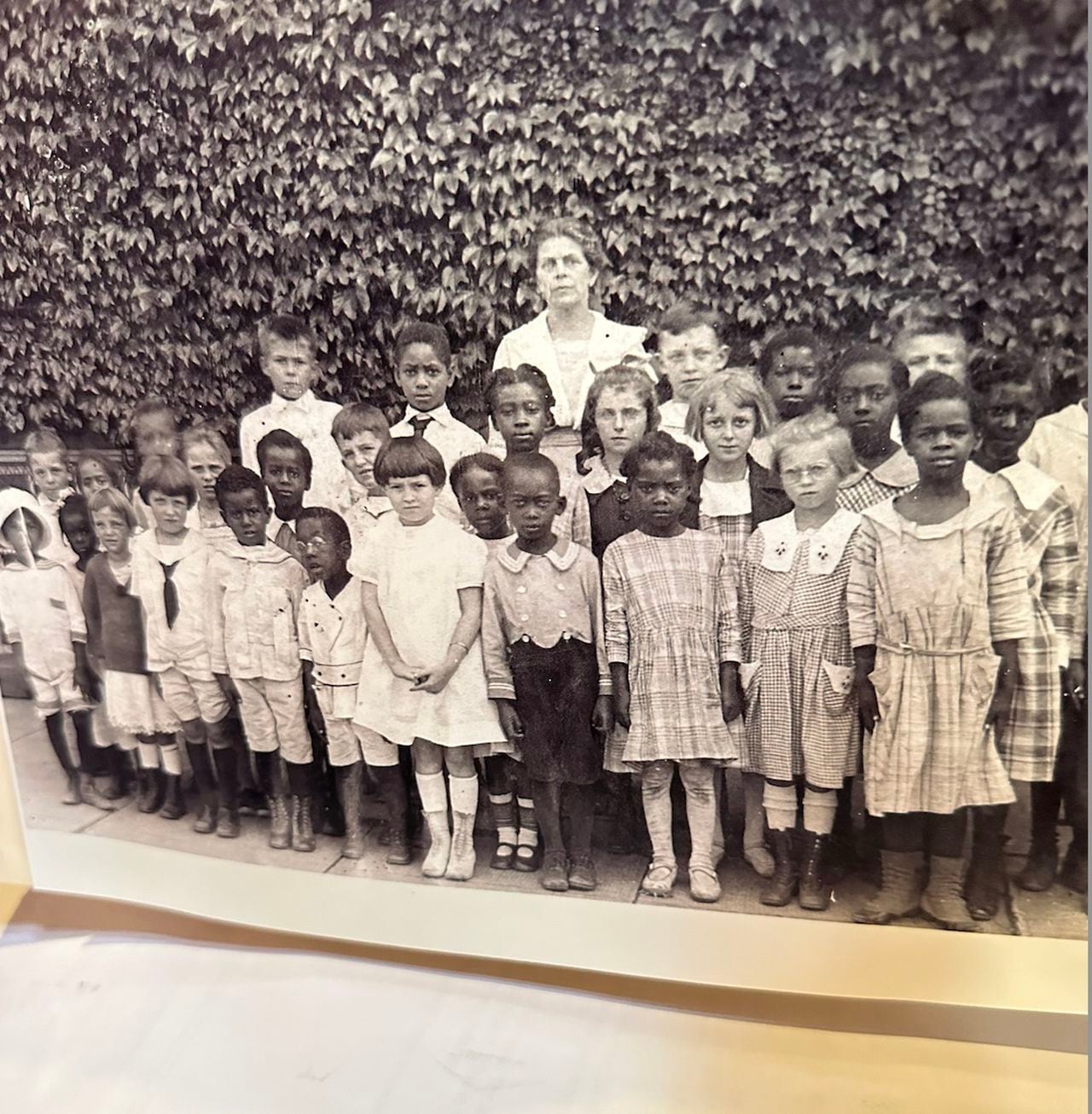

School children from Sandy Ground and nearby communities in Pleasant Plains, circa 1921. (Courtesy of Julie Moody Lewis)